JOHN (JACK) HENSEL: MY FRANKLIN STORY

INTRODUCTION

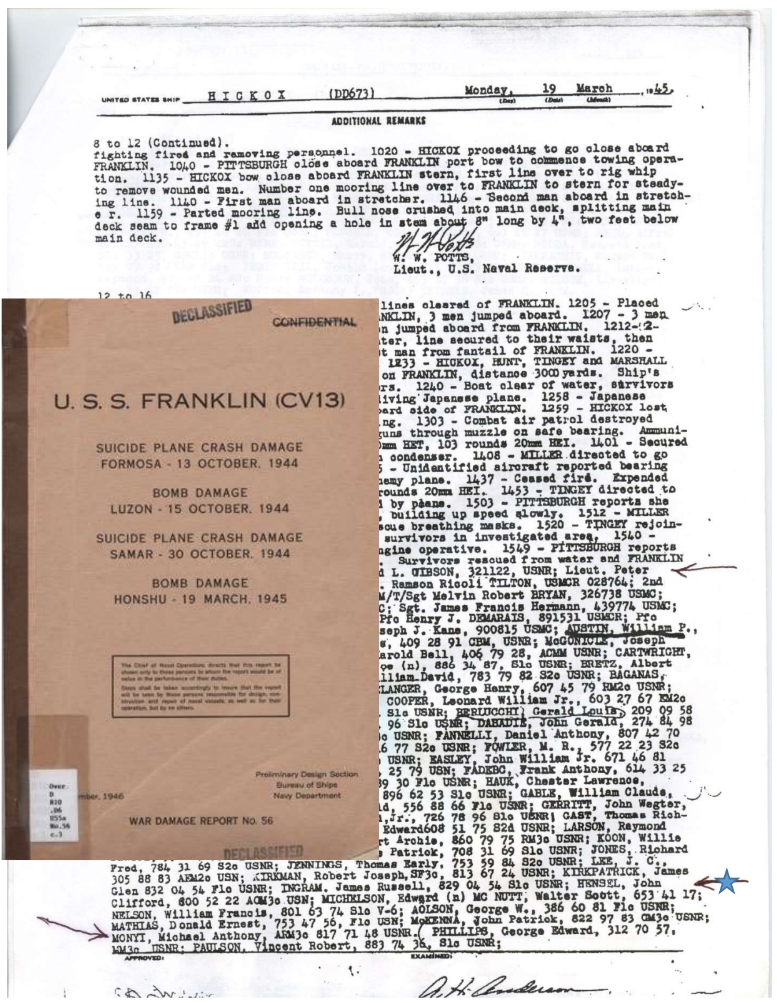

It has been my pleasure to help bring John (Jack) Hensel’s story to publication. His account brings a personal focus to the historic events of March 19, 1945 on board the USS Franklin. Jack tells a compelling narrative of a first-hand experience that needs to be told and retold. The Franklin is often referred to as “the ship that wouldn’t die.” While that is true for the ship, it isn’t for the over 3000 crew aboard her that fateful March 19 as over 800 were killed and another 200+ injured. Jack Hensel was among those wounded, and this is his story.

Debbie Horneski

CONTENTS

Jack’s Story

Hickox Wounded Roster

The Valiant, Squadron VT5

Franklin Poem

Biographical Data

Tribute to Grandfather

Sources

On March 19, 1945, I was aboard the U.S.S Franklin. The events of that day led me to a

prolonged stay on a medical ship. I had plenty of time to think about the circumstances which brought me to this unexpected place. In my own words, this is my story.

I was inducted into the United States Navy on June 22, 1943. I received my high school diploma on June 23, 1943. I reported for naval duty on June 29, 1943. So, you see, they didn’t give me much time after my high school graduation. The navy wanted us badly!

My first duty was the naval station for boot camp at Sampson, New York. There I went through marching, swimming, discipline, calisthenics, medical physicals, shots, aptitude tests and interviews. It was also here that I volunteered to fly as an air crewman and given a flight physical which I passed.

I remember going to the chapel one week before graduation from boot camp. There they announced that all leaves were cancelled; usually we got a week leave after boot camp. I saw men coming out of the chapel crying. I started thinking that there was a big sea draft coming, and it surely was upsetting. We did get our leaves but after an extra week of training.

I was sent to Aviation Ordinance School in Memphis, Tennessee. I graduated in January 1944 and went to Airborne Radar Operations School at the same base. The school lasted about two weeks. I could have stayed on as an instructor, but I did not want to. Our instructor wanted to give it up at that time, and he had to look for someone to take his place.

I finished radar school and was sent to Hollywood, Florida for Aerial Gunnery School where we learned all about the 50-caliber machine gun, trap shooting for learning how to lead the targets, and operating the gun with the ball turret firing both at range targets and at targets being towed by planes.

After about six weeks of Aerial Gunnery School, I was sent to what the navy called operational training at Fort Lauderdale, Florida. This is where I started flying in TBF Avenger torpedo bombers and also where a lot of interesting things started happening. We were taken to a TBF that had crashed in the everglades. The plane didn’t burn but did sink nose-first into the mud, up to its wings. This sight was very scary.

At this point, I was assigned to a crew: a pilot, Ensign Fuller from Boston, Massachusetts; a radioman, Robert Jensen from Salt Lake City, Utah; and, myself, a turret gunner from Utica, New York. We would supposedly stay together throughout combat.

The first time in the TBF plane, at my position in the turret, I could observe the tail section very well. The engine was started and smoke poured down the side of the plane from the exhaust. The engine ran very rough on starting, and I could see the tail section shake and vibrate because of the engine running unevenly. I wondered, “What did I get myself into?” Once the engine warmed up, it ran smoothly. We took off, and it was excitingly pleasant.

We had many interesting flights practicing torpedo runs, gunnery firing at slicks in the sea and at targets being towed by another plane, navigation flights and glide bombing. Glide bombing was quite exciting. We would rise to about 10,000 feet, and the plane would nose over. So help me, we would dive at a vertical angle 90 degrees to the sea for a quite a length of time, and then pull out of the glide at about 1,000 feet. We practiced this quite often.

On one of the torpedo run flights, I asked the pilot for permission to operate the ball turret. I was just able to get into it because it’s like getting inside of a large ball. With the turret down and the 50 caliber machine gun pointed to the rear of the plane, I could easily get out of it by letting down an armor plate and dropping down into the radio man’s compartment. I turned on the turret, and it malfunctioned. The gun pointed straight up into the air perpendicular to the body of the plane, and it wouldn’t come down with the control. Here I was in the ball turret on my back with no way to get out, only possibly through the side panel. I reported this to the pilot, Fuller, and he asked if I wanted to go back to the base. I replied, “No, go on with the flight.” After about 1 1⁄2 hours, we landed back at Fort Lauderdale Naval Air Station. The ground crew observed us landing with me still in that position and came right out to the plane. They took off the side panel of the turret and were able to wiggle me out of the turret. At my age then, 19, it did not bother me. Since I would get into the turret from the radioman’s compartment, my radioman, Robert Jensen, said, “Jack, if this same thing happens to the plane, don’t expect me to ride the plane down with you – I’m jumping.” I could never do this today because I couldn’t even fit into the turret. I don’t even think I could fit into the side opening of the plane into the radioman’s compartment.

On returning to the airfield and entering the landing circle, there is a point where the pilot puts down the retractable wheels and lowers the flaps to lower the speed and get additional lift. These are operated hydraulically. We had an exciting experience returning from a night flight. On entering the landing circle my pilot, Ensign Fuller, tried to lower the landing gears and flaps. There was a hydraulic leak; the wheels appeared to come partially down and one of the flaps came partially down. The flap acted as an aileron causing the plane to lurch to the side. My pilot was able to adjust with the regular ailerons. He stated later that he never takes his hands off the flap operating lever until they are completely down. Feeling the jolt of the plane, he quickly returned the lever to the flaps-up position and the plane resumed normal flight. If he hadn’t done this, the plane would have banked, lost speed, and dove to the ground. At this point, I remember flying over the Fort Lauderdale water tower. (You are that low when you are in the landing circle.) There was hydraulic fluid all over the plane. The pilot was instructed to gain altitude, dive the plane, and try to snap down the landing gear. He also had a hand pump in the cockpit to force the wheels down. He did this, and he made the same low passes over the Fort Lauderdale control tower. They observed this and instructed him to make a flaps-up landing which meant landing at a higher speed. We held our breath, and made the landing safely as we passed the rescue squad on the runway waiting for us. This was exciting, especially at night.

We graduated from operational training toward the end of May 1944. At graduation, the

crewmen proudly accepted their Air Crewmen Wings. Our crew was assigned to Torpedo Squadron 5 (VT-5), a part of Air Group Five.

We were also given delayed orders for San Diego, California which meant we had about 30 days at home. During this time, the pilots were sent to the Great Lakes to practice carrier landings on a small carrier there. I arrived home for my leave on DE Day the beginning of June, the day of the invasion of Europe. After my leave, I went by train to San Diego, California where I met several crewmen including my radioman, Bob Jensen. We stayed at San Diego Naval Air Station (NAS) for one or two nights, and then received our orders to go to Alameda, California NAS where we would join our pilots and the rest of the VT-5 Torpedo Squadron. At the chow hall, I got my tray and food. I walked to a table, sat down, and looked across the table. Getting ready to sit opposite of me was an old family friend and a good friend of my brother Pete. We caught each other’s eye and hands came across the table; it was Alfred Camhellack. He said, “Jackie Hensel, what are you doing here?” I told him, and he seemed sorry to hear that I was an air crewman and would eventually be on an aircraft carrier. He had just come off the carrier USS Intrepid which was torpedoed by the enemy in the South Pacific. I went out that night with Al and a friend of mine, Dew Hontz. We had a few beers, talked about home, and returned to base in fairly good condition.

The VT-5 squadron stayed at Alameda for a short period of time and then was sent to Monterey NAS, California to begin our training as a group. When there was no fog, we would do a lot of flying. We stayed here for several weeks and then transferred to Santa Rosa NAS, California where we remained for our duration before boarding the carrier. We did go off to different bases: Eurica, California for rocket training and Modesto, California for night flying. We flew many navigational flights out to sea. One time we thought we saw the image of a submarine below the surface of the sea. I’m sure my pilot reported this, and it was investigated by surface craft. Another time we were far out to sea on a navigation flight, and we spotted a freighter headed toward San Francisco. My pilot passed over it but we didn’t have our IFF- a signal identifying you as a friend or foe. There were a couple of tracer shells fired in front of us as a warning. The crew on the freighter probably had a chuckle or they may have been jumpy just coming from a combat zone. The squadron did a lot of flying out of Santa Rosa practicing night flying, air group hops, navigation flights, etc. Ensign Fuller, my assigned pilot, developed knee problems and was transferred out of the squadron for other duty.

While waiting for my new pilot, I made a few flights with several pilots whose crewmen had not yet arrived. On one of these flights, we were the last to land with this particular plane. We landed in the morning, and there was a flight scheduled with this plane in the afternoon with another crew. When they returned to the airfield and got into the landing circle, the plane suddenly dove from this low altitude and crashed between two homes. The plane burned, killing the crew. The aircrew names were Klingman and Allman. The report said it was mechanical trouble. It probably occurred at the point where the wheels and flaps would be put down. I felt there may have been a hydraulic leak on one of the flaps that didn’t function. This acted as an aileron causing the pane to flip on its side, lose speed, and dive into the ground. I think of this frequently as a similar incident happened to me in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

Lt. J. J. Gibson, my new pilot, arrived and I began flying steady with him. Also a new radioman, Louis Lyndenmeyer, was assigned. We had a lot of thrilling flights with him hedge-hopping at tree top level, flying along the seawall. I remember looking up at it and flying low over the San Francisco Bay and seeing a man fishing in a boat standing up looking at us- we were that low. Some farmers called in complaining about the hedge-hopping because we were disturbing their cows. On one occasion, we took off and gained just a few feet of altitude and the engines started skipping as we skimmed over the top of a chicken farm. I remember the chickens fluttering inside their coops. We were able to make it to an auxiliary airfield not far from the main field. It was found that the gasoline tank was partially filled with water because of condensation. It was cleared, and we flew back to the main base. We went to Modesto, California for night flying training practicing group flights on imaginary targets. The pilots, less the air crew, practiced night touch-and-go landings. On one warm night, we were standing as a group in front of the barracks when we heard the sound of a crash. We rushed to the runway and watched a plane burn; the pilot was killed. This left a terrifying impression on our minds. When we went to Modesto, we realized that night flying was really dangerous. Soon after, we were ordered to Eurica, California for training in firing five inch rockets from the plane. We were there for about two weeks and then returned to Santa Rosa.

I realized the time was approaching when I would be assigned to an aircraft carrier. In December 1944, I received a week’s leave just before Christmas. I did not have enough time to go home. My squadron yeoman friend, Gerald Nold, invited me to come home with him to Arkansas City, Kansas. To get there and return, we rode the train and hitch-hiked, often getting rides with truckers. I had a fine time meeting his family and girlfriend. (Nold was later killed at his station in the pilot’s ready room when we were hit by Japanese bombs on March 19, 1945.)

I spent New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day in San Francisco with another friend, Elmer Lowery, from Covington, Kentucky. (He was also killed on March 19, 1945.) We spent New Year’s Eve having dinner, visiting night clubs, and mixing with the crowds on Market Street there. On New Year’s Day, we went to the East-West shrine football game at Kesar Stadium in San Francisco. It was quite a sight with the crowd and the excitement of the game. I remember the street cars and people hanging on to the side and back of them to get to and from the game.

We spent most of January getting ready to go overseas, getting new planes, and other necessary gear. We went aboard an old carrier, the USS Ranger, out of San Francisco. We traveled out to sea getting used to carrier operations and life aboard a carrier.

building dock. October 14, 1943. Photo courtesy of Naval

History and Heritage Command.

We returned to Santa Rosa continuing air group flights and getting ready to board an

aircraft carrier. We boarded the USS Franklin he first week of February 1945 in Alameda, California. I remember pulling away from the dock and feeling the waving of the ship on the bay. We sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge and a sailor’s girlfriend tossed part of her clothing which landed on the flight deck of the carrier. After leaving the Golden Gate Bay,

there were swells in the ocean causing sea sickness to many sailors until everyone got used to the swells. I remember having to lie on my bunk for a time on the bow end of the ship because lying down seemed to help the sickish feeling.

We got to go to Hawaii and docked at Ford Island and could see the hull of the USS

Arizona which had sunk because of the December 7, 1941 Japanese attack. We went

to Kaneohe NAS for continued training while the USS Franklin was being fitted for combat. We had several flights over the islands and the pilots practiced touch-and-go landings. This was also the Sea Bee base, and we had tremendous meals and spent time playing volleyball, softball and entertaining ourselves.

We boarded the USS Franklin around the first of March with a full complement of Air Group 5. The fighter squadron F4U Corsair fighter planes and some Marine Squadron were reminiscent of Pappy Boyington’s Black Sheep group. The bomber squadron VB5 was made up of SB2C Helldivers and my squadron VT5 the torpedo bomber squadron TBF Avengers. We performed many air group training missions and navigation flights on the way to Ulithi an anchorage where task groups assembled. We arrived at Ulithi early in March, the morning after a suicide plane struck a carrier, either the USS Randolph or the USS Hancock. We stayed at Ulithi one night and as far as I could see there were ships of all categories: troop ships, supply ships, tankers, battleships, carriers, destroyers, etc.

Japanese hit. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

We left Ulithi with carrier group 58.2 on our way to Japan to raid the main islands. We were the first ship to carry the new rocket called the Tiny Tim. These rockets were equivalent to the shell of a 16” gun fired from a battleship. On one of the first times I took off from the Franklin, I was catapulted. Our crew was not given any pre-warning. We were ordered from the ready room to report for a flight with our pilot and to be catapulted. There was no time to think about it. We boarded the plane and proceeded to catapult position. There were crewmen from the old VT5 squadron. These were men who had already been in combat duty. They were there to give us instructions on how to hold our heads at the moment of takeoff. It was such a sudden jolt your head would jar if you didn’t hold it in a special position. The pilot had to hold his head back against the head rest as he was looking forward. The radioman, also looking forward, had to put his head down between his legs. I, the turret gunner who was riding backwards, had to hold my head and bend forward under the gun sight. The pilot would rev up the engine to flying speed and suddenly you would gain altitude quickly and go from 0 mph to 85 mph in about one hundred feet. I would be looking down at the end of the flight deck.

Landing on the carrier was quite an experience. We had a SB2C dive bomber miss the arresting gear and go off the side into the sea. The radioman gunner was killed, but the pilot survived. We also had a TBM torpedo bomber go into the sea as it was attempting to land. The pilot survived; there were no crewmen aboard. I had some scary landings. One time we landed and were off at an angle, but the landing hook caught the arresting cable and stopped us just before going into the sea. I looked to my right out of the turret, and I could see the water and some members of my squadron on the catwalk holding their heads. Another time we landed straight but very hard. The hook caught the arresting gear cable. The plane bounced high and came down hard blowing a landing gear tire. My head jarred and the gun sight hit my nose, cutting it slightly.

On landing, I could look over my right shoulder and see the direction of our flight toward the carrier. We would be flying directly over the churned wake of the Franklin about 100 feet above the ocean. As we approached the rear of the flight deck, I could see the landing signal officer giving my pilot instructions by the way he waived his flags. He signaled whether we were flying too low, too fast, too high, to bear left or right and the timing with the up and down movement of the flight deck. If all instructions were not right, we would get a wave-off. The landing signal officer had a net off the side of his position on the flight deck. He could jump into the net if a plane got misaligned and came too close to him. On one attempt at landing, we took six wave-offs for various reasons. I remember going along side of the carrier after one of the wave-offs looking up at the signal officer with his hands on his hips watching if we would go into the ocean. So, you see, there were all kinds of risks even before combat.

The planes are spotted very close together on the flight deck before a mission takes place. On one occasion I was late in getting to the plane on one of those surprise flights. I was in the middle of the flight deck on my way to our plane when it was announced for the pilots to start their engines. I was just a few feet from spinning propellers, but one plane captain spotted me and expertly guided me to my plane.

While on our way to Japan, we still were training with air group and navigation flights. On one occasion when our crew was out on an anti-submarine flight and had an escort of one of the F4V fighter planes, we flew in very close formation. I felt I could almost reach out and touch a fighter plane’s wing tip. I was amazed that fighter planes traveled in such close proximity. I could see that one of the fighter pilots was laughing. We waived and showed gestures to one another.

At night time, as we neared Japan, there was a lot of suspense with general quarters signals and orders coming over the loud speakers and lights going on and off as hatches were opened and closed. The enemy was dropping flares to silhouette against the sky so they could find us and attack. The night fighters must have taken care of them as we were not attacked at this point.

Our first bombing raid was on March 17, 1945. Our crew was not assigned to this mission. I remember the pilots singing Happy Birthday to Lt. Carr, our executive officer. He was also he leader of this first flight.

The next morning March 18, 1945, on my 20th birthday, our crew was assigned to this day’s mission. Many of the air crewmen sang happy birthday to me. We took off and had to fly through heavy thick clouds. When we finally got above the clouds the three plane group we were with was miles behind the main air group. We caught up to them just about the time Japan came into sight; we went to 25,000 feet and were on oxygen. We would be raiding an airfield on the west coast of Kyushu at Kagashima Igumi the southernmost island of the mainland of Japan. We flew across the middle of the island at 25,000 feet on oxygen. I could see cities to the north and south of us. We started our glide bombing run. I could feel the ice on the inside of my oxygen mask and the change in temperature as we dove. My radioman was dropping reflective confetti, as well as the plane in front of us, to deter the enemy’s radar controlled anti-aircraft guns. As we dove, I saw our port wing tip and reported this to my pilot. Looking over my right shoulder, I could see where we were headed. As we drew closer to the ground, my pilot fired his wing machine guns and dropped the bombs which appeared to hit an airfield hanger. I saw much debris like clapboards and parts of the building exploding into the air along with the flames and the smoke. We pulled out of our dive, and we were only about 150 feet above the Japanese airfield. We came out over the China Sea and there was one of our surfaced submarines a few hundred yards off shore. It was moving and ready to pick up any survivors from planes that were hit and had to ditch into the ocean.

We regrouped and started back just south of Kyushu Island. I observed many Japanese freighters sinking and on fire. Fighter planes were strafing the many ships at this point. The splashes from the guns of the diving fighter completely hid some of the smaller ships.

We got back to our carrier and my pilot made a perfectly smooth landing with no wave-offs. We got out of our planes and headed for our ready room. We were instructed over the loud speaker to hurry off the flight deck as there were enemy planes in the area. We got back to our ready room and realized the effect of the flight on us, the anxiety and nervousness, as well as the relief of getting back safely. I remember describing our mission and getting a shot of whiskey.

I was scheduled to fly a combat mission the next morning, March 19, 1945. I was awakened at 3:00 A.M. for an early breakfast. I reported to our ready room to get briefed and ready for the 6:00-7:00 A.M. flight. I was all ready to fly. I had on two or three pairs of pants, two or three layers of shirts, my leather flight jacket, heavy shoes and my “Mae West” life jacket. Just before boarding the plane our crew was cancelled because they needed a radioman with electronic radar interference experience. Since I was all dressed to fly and had eaten breakfast, I decided to go out to the flight deck catwalk and watch the planes take off. All the fighter planes were airborne and about half of the VB5 bombers were off. The torpedo planes were behind the bombers and were the last to takeoff. Since it was cold, the carrier was going into the wind at the top speed for take-off operations. I was thinking of going to the coffee station we had in our ready room to warm up. I came back out in time to see the torpedo bombers take off. I waited and watched a couple of bombers take off. I just started leaving the catwalk to head under the flight deck to our ready room when there was a terrific blast. I put my hands to my face at this sudden blast; flames came and then the dense smoke. I could not see my hands in front of me. I backed off and felt myself passing out from the heat of the flames, the concussion from the explosions, and being unable to breathe because of the dense smoke. Then came a split second when the air cleared, and I caught my breath. Then there was another explosion; again I was enveloped in flames, dense smoke and an awful confusion. I went to the top cable guard of the catwalk, and then there were a series of explosions with no letup of the smoke. I had my stomach up against the top cable, and as another explosion came I rolled over the cable and dropped into the ocean 90 feet below. I must have been knocked out. When I came to I was deep in the ocean as I could not see anything but darkness. I looked up and could see the glitter on the surface of the ocean. I thought afterwards that with the carrier going at top speed and with me dropping close to the hull of the carrier that the ship’s propellers could have drowned me deep into the sea.

This all happened without any warning; we were not at general quarters. I did hear some gun fire a second before the initial explosion. I did not get an explanation about the Jap plane, a Judy bomber, coming in low out of the low hanging clouds and too low for radar to pick up until I was on the destroyer. It dropped two 500 pound bombs on us. This acted as a fuse to ignite the gasoline lines that were lying on the decks, the remaining planes that were loaded with gasoline, bombs and rockets. The Judy was shot down by air group commander Cameron Parker who was aloft and flying an F4U.

After coming to in the ocean, I kicked and swam to the surface. Here I was with all of this heavy clothing and shoes on and still with my steel helmet strapped under my chin. My first thought was that I was alive and survived. I immediately thought of my nephew Peter John Hensel who was born on January 28, 1945, and whom I had never seen. This seemed to put some survival fight into me. I struggled and stayed afloat. I remember seeing the burning carrier going away from me. I remember several sailors popping to the surface with me. They had a strange stare with no expression and in my struggle they just seemed to disappear. I thought afterwards they must have been killed. For a few moments, I felt all alone in the wide ocean and scared. The ocean was very rough that morning. I remember seeing the bows of ships coming completely out of the water. I reached the peak of a wave, and then about a hundred feet from me was a raft. It must have been blown off from the explosions. As I got near the raft I recognized a sailor, Mike Monte, from the bomber squadron VB5. Then a ways off the raft was my pilot Lt. J. G. Gibson. He was on his back and appeared to be semi-conscience with some blood around his mouth. I observed as crewmen Monte dove off the raft and pulled Gibson to the raft. I got to the raft about the same time as they did and helped Monte get Gibson to the raft. About this time the bow of a battleship approached, USS North Carolina #55 (BB55). It was so close that someone from the bow dropped more life preservers for us.

I visited the battleship BB55 that is on display in Wilmington, North Carolina. In the battleship’s trophy compartment, there is a picture and a note telling how they were in the same group as the Franklin on March 19, 1945. The note explained how the BB55 captain ordered a sharp turn to avoid survivors of the Franklin. Thank God someone observed us enabling the captain to give the order!

Monte had hollered to me to pull the cord to inflate my “Mae West” and to throw off my steel helmet as it was coming down over my eyes. This ended my struggle to stay afloat. He hollered before I had gotten to the raft. The wake from the battleship made it difficult to hang onto the raft. It finally settled down. It was then that I noticed the burns on my hands; the shock of the event must have dulled the pain of the burns. I saw a small amount of the blood coming from the back of my hands. I then thought of sharks which gave me the strength to push up onto the raft.

After I got into the raft, I saw that a semi-conscience Gibson was on the edge of the

donut-shaped raft. He slipped into the center and disappeared under the water. Another survivor and I were able to grab him and pull him back onto the raft. In the center of the donut-shaped raft, was a rope net that hung below the raft. I wondered what would have happened if Gibson had got tangled up in it or might this have kept him from going way under. In the meantime, a man I did not know climbed onto the raft which made four of us.

Soon I saw the bow of a destroyer, the USS Hickox DD673, heading toward us. The bow was coming completely out of the water. I remember saying if I see the bottom of the bow I’m jumping, thinking that the bottom of the bow would come over the raft and take it under the ocean. As the destroyer approached us, the captain must have ordered the ship into reverse as this held the bow down as it hit the raft. The fourth man on the raft fell off and was picked up. A line was thrown, and I caught it. The ship must have been moving forward as I hung onto the line which pulled the raft along the ship. The sailor on the other end of the line kept letting line out and, we ended up a ways from the ship as it stopped. We were pulled up to the port side of the destroyer where there was a cargo net and sailors aided in pulling us off the raft and onto the destroyer. They took us to a central compartment on the main deck and there was a doctor on board. Lt. MC R. K. Williams, a sailor from the destroyer, dove into the ocean and pulled in a survivor that was severely burned. The doctor was working on him and directing corpsmen that were working on Monte and me. Gibson must have been taken to another compartment.

Corpsmen took off our wet clothes and put us in in clothes from some of the ship’s company or what they called small stores. They cut off my high school ring. We started to shake either from coming out of shock or from the cold. I remember holding my hands down and fluid kept coming out of them. I could not stop shaking. The corpsmen sprinkled sulfur powder on my face and hands. They bandaged my hands with Vaseline gauze, and I had several patches on my face. I don’t remember any pain until after I stopped shaking and being bandaged. It must have been because of the trauma and shock of the incident. My eyelashes and eyebrow hairs were all burned off. There were other blistered and crusty areas to my face besides the deep burns. After a while, they sent Monte and me to an officer’s compartment to recover from the shock. The man the doctor had been working on died the next day and was buried at sea.

The Hickox pulled up to the fantail of the Franklin. There were many sailors trapped on the fantail from the fire and explosions. The sea was still rough and as the bow of the destroyer rose up near the fantail the men trapped there were jumping off onto the bow of the Hickox. One missed the bow and fell into the sea and was rescued. While this was taking place there were still explosions and rockets taking off from the Franklin.

Japan. Note fire hoses and crewmen on her forward flight deck and water

streaming from her hangar deck. Photographed from USS Santa Fe.

The cruiser Santa Fe pulled along the star board side of the Franklin, and I understand they took on the remainder of Air Group 5 and personnel that were wounded. I observed the cruiser Pittsburgh take the Franklin in tow. The Hickox was firing at Japanese planes that were trying to finish off the Franklin. I was disappointed when I woke up the morning of March 20, 1945 and found that we had not proceeded very far as the Franklin was almost dead in the water. The Hickox just circled the Franklin all night.

After many hours of continuous duty the officers wanted their compartments for sleep, so we were assigned bunks in a compartment in the bow of the ship. I could stick out my arms and touch both bulkheads. The sea was still rough and the greatest movement is at the bow end of the ship. So help me, with the vast up and down movement, I would lift off the top of the bunk as the bow dropped. I had to balance myself with my elbows as my hands were bandaged.

If I had not gone to early breakfast, I might have been in the chow line where all were killed. If I had gotten back into our ready room for coffee, I would have been there when the first bomb dropped. There was only one that escaped alive from there. I am glad I did not go when I first thought of doing it.

The Franklin along with the destroyer group arrived at the Ulithi anchorage on March 24, 1945. I was put over the side of the Hickox in a basket to a motor launch and transferred to the USS Relief AH1, a hospital ship. It was either Palm Sunday or Easter as I remember going to a church service. I spent one night on the Relief AH1 and then transferred to another hospital ship, USS Bountiful AH9. The Relief was ordered to proceed to Iwo Jima to care for the wounded there as the island had just been secured.

It was a great feeling to get aboard the hospital ship. On the Bountiful I met two friends from my squadron: Drew Hontz from Wilksbarre, Pa and Knudson from Philadelphia, Pa. Knudson had ear drums injured from the concussions of the explosions. Drew Hontz had an odd bone broken under his collar bone and was transferred after a two day stay. I remember Drew Hontz going over the side of the hospital ship in a basket. I can still see his smile and the wave he gave me— the great feelings of survival!

Knudson said he would give me a shower but would not clean my crotch, as if I would let him. I held my bandaged hands over my head and he soaped about 90% of my body, and I rinsed myself. It sure felt good to get the shower. Knudson also wrote a letter I dictated to him for my parents explaining my wounds and telling them that I was safe. Since the tips of some of my fingers extended through the bandages, I was able to put a mark on the letter.

The USS Bountiful was anchored close to the Franklin. I could see the blackened area and massive hole on the port side about where I was standing. Our air group flight surgeon examined me leaving me aboard the hospital ship while the rest of the air group went on. He informed us of the many that were killed from our squadron. I lost two close friends: Elmer Lowery and Gerald Nold.

After about two weeks, I was released from the hospital ship and sent to a transfer ship the USS General Bundy APA93. I was put in a launch as we pulled up alongside the General Bundy. I had to climb a cargo net, which looked to be about forty feet high, to get aboard. It was a tough experience trying to pull myself up with my yet tender hands. I spent about three nights on the General Bundy and slept in a compartment about six decks below the main deck. I was then transferred to a CVL, an aircraft carrier just a bit smaller than the Franklin class, either the USS Princeton or the USS Cabot. I was headed back to the USA.

We stopped at Pearl Harbor for a day or two. I had no clothes and no money. My gear was an extra shirt, pants, and underwear that a crewman gave me somewhere along the line. I had no identification with me. I went to the officer of the deck and explained my situation and asked him if I could go ashore at Ford Island for a while. He let me go but warned me to get back in a short time as his watch would be ending, and the next officer of the deck would not recognize me.

We left Pearl Harbor and proceeded to San Francisco Bay under the Golden Gate Bridge. What a welcomed sight it was! We docked at Treasure Island in the bay, and I was immediately transferred to Alameda NAS.

I originally wanted to get back to my squadron but my orders came through for a thirty day survivor’s leave and then on to Naval Air Technical Training Command (NATTC) Norman, Oklahoma for a refresher course. I received a complement of new clothing and my back pay. I was happy and looking forward to my trip back home.

While at Alameda I met a former member of our squadron, Smith, a radioman. He was being transferred to Rhode Island to train for night duty with radar and then overseas. He spotted me, and I gave him the names of the men that I knew at that time who had been killed.

After my leave, in June 1945, I arrived at Norman, Oklahoma. I asked and received a weekend leave and was able to visit the family and friends of my friend Gerald Nold in nearby Arkansas City.

I was accepted for pilot training but the atomic bomb was dropped, and the war ended. I elected to leave flight school as we had just begun the refresher course. I was transferred to several bases ending up at Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn and was discharged from Lido Beach, Long Island in April 1946.

Here are some afterthoughts…

The sound of the initial explosion was unexpected and a devastating experience. It came so sudden with the flames, smoke and heat. That second surely changed my life and attitude. It is just hard to explain the effect and the shock it put me into. The one second that the air cleaned before the second bomb exploded gave me breath and probably saved my life as I was feeling faint.

Ardell Lietzke broke his leg and was in a cast. He broke it playing softball sliding into second base. I was the one who threw the ball to try to get him out. He begged the doctor to let him stay with the squadron. The doctor did so against his better judgment because he had to put a cast on Lietzke’s leg. Later, on that fateful date, Lietzke went into the ocean. He was unable to stay afloat with the cast on his leg and drowned. The doctor stated when he examined me that the decision he made about Lietzke was something he would regret the rest of his life.

I regret that I was only able to be overseas for just a short period. Yet, when I look back, the events of March 19, 1945 were so traumatic that it gave me the feeling of contributing to the war effort.

I regret now that I put this experience of being wounded and getting split up from the remaining squadron in the back of my mind. I didn’t express this experience throughout the years and did not keep in contact with these men. I also regret not maintaining contact with Gerald Nold’s family and friends. After being discharged and returning home, this experience was put into the back of my mind while I socialized with my family and friends but it has never been forgotten.

A final thought…

I came into my kitchen about 9:00 a.m. on September 11, 2001 and the television was

on. It showed the World Trade Center, North tower, burning; an airplane had just run

into it. I kept watching the television and saw the second plane hit the South Tower. I

observed the flames and smoke as it hit. I could imagine the people in the building at

that second going through quite the same of what I went through only having nowhere to escape.

The Men of the Franklin

On March 19, 1945, the Japanese dropped two bombs on the USS Franklin. Below are the names of the men killed from my VT5 squadron whose faces I will always remember…

ENS. Glenn Drulinger

ADM3C Elmer Lowery

ACRT Raymond Pagel

CCDR Allan Edmunds

ARM3C Ray Hute

ACRM Charles Jenkins

ENS. Patrick Lacy

ARM3C Robert Wakefield

ARM3C Robert Baucum

ENS. Charles McAllister

ARM1C Theodore Dorak

AOM1C James Hobbs

ENS. Julius Watson

PRIC Gene Smith

AOM1C Howard Stone

LTJG David Evans

ACMM Gordon Lyons

AOM3C David MacLeod

ENS. Wilman Wheeler

Y1C Donald Kenfield

ARM2C Ardell Leitzke

Y3C Gerald Nold

ARMIC Loyd Fairbrother

ADM1C John Matysyn

LT George Watkins

Men of the Franklin

Praise for the men who fought

The FRANKLIN’s cause to win,

But for Her dead, a thought,

May memory take them in!

May memory hold them dear,

Her thousands maimed and dead!

To Freedom’s utmost year

May prayers for them be said.

At fearful post they stayed,

Let history’s ages note,

Gallant and unafraid,

Keeping the ship afloat!

Praise for the Living, aye!

For ages be it said,

But, as the years go by

Remembrance of her dead.

Edgar A. Guest, 1945

BIOGRAPHICAL DATA: JOHN (JACK) HENSEL

Parents: Peter W Hensel and Matilda Wolff Hensel

Born: March 18, 1925; Utica, New York

Sibling: older brother, Pete

Education: Utica City Schools

High School Jobs: Boston Store; local lawn care

High School Graduation: Utica Free Academy, June 23, 1943

Naval Choice: uncle in navy; always interested in model airplanes

Naval Induction: June 22, 1943

Discharged: April 1946

Military Award: Purple Heart

Marriage: To Mary Elizabeth Follette, October 1, 1945

Children: Richard, Jill, Mary-Lynn, Nancy, John, Mark; 15 grandchildren; 8 great-

grandchildren

Post-Military Employment: traveling heating and plumbing parts salesman

Retired: May 1988

Today: active member of USS Franklin reunions and correspondent with Franklin

families; member of Military Order of the Purple Heart, Chapter 490

Excerpts from….. “A Tribute to My Grandfather”

I have nothing but fond memories of my grandpa. I can remember going to so many

different places with him. We’ve gone to visit different war memorials and out to dinner

and ice cream many times. Every time we do go somewhere with him it is always fun and

I end up laughing and having a great time.

He’s been through a lot of things in his life and one of the most admirable was his

commitment to the United States Navy and his participation in World War II. I look up to

him for not only this reason, but many others as well.

In October of 2009 my dad’s family and I attended my grandparents’ 60th wedding

anniversary. As always at family special events, I make sure that I dance with my

grandpa because I know it brings him joy as it does to me, after all he won’t be around

forever and I would like to cherish every moment I have with him.

He is very proud of us all, and I am very glad that I can call him my grandfather.

By Your Loving Grandchild

SOURCES

http://www.ussfranklin.org

http://www.cv13.com

Http://navysite.de/cv/cv13.html

http://www.navy.mil/navydata

navy.mil/submit/navyStyleGuide.pdf

Naval History and Heritage Command Photo Collection

Fox6now.com